Phd Research Proposal

The Evolution of Digital Processes and Materials.

Is Peer-to-Peer the beginning of the end of capitalism as we know it?

George

N. Dafermos

Table of Contents

Academic Importance and Relevance to Social Science

Hypothesis

-

Schumpeter: Capitalism is subject to Creative Destruction

A Case of Creative Destruction: Music Wars

Yet Another Example of Creative Destruction: Enter the Telecoms Industry

Massive Turmoil and Institutionalisation

2. Making Sense of Peer-to-Peer

2.3 Social and Political Organisation

2.4 Economic and Industrial Organisation

Methodological Framework and Data Collection

Personal In-depth Semi-structured Interviews

Literature Review

: Evolutionary Economics

Planning of Research and Publications

2. Constraints to the Completion of the PhD

**********

Human organizational structures like the so

called "free market Capitalism" are dynamic

complex manifestations of the

evolutionary advancements in digital materials and processes

overlaid

with the mythical values of current

or past cultures including the delusions of infinity related to the Earths resources. Thus it

follows the creation of an

irrational and incoherent global

monetary system of unrealistic values

disconnected from the realities of the finite conditions of the natural

world on which our survival depends. The

values of the current global monetary system do not reflect the factual costs to environmental quality and

fail to address the issues of global

warming and so they are at their

base irrational. The irrefutable fact that we are

currently in a phase

of negative global consumerism with rates of consumption that can

not be sustained is incoherent and unethical. The

unrealistic values that do not

reflect the value environmental quality and fail to address the issues

of global

warming is a human tradagy. It is an irrational,

incoherent and unethical global monetary system that

almost

exclusively creates monetary

value for the few at the loss of digital

freedom, human rights and environmental sustainability of others.

Current globalism as practiced is not sustainable,

however global finical structures and centers of control like the World

Trade Orgnazation, IMFL are now in

place and it is possible in time that these global structures could

evolve into sustainable systems, but only if the finite

nature

of resources on the space ship called earth are acnowlage and

become the underpinnings of mans ethical behaviour. Now, for the

first time in the world's history, a single species has developed the

technological means not only to exploit the resources of all the

Earth's ecosystems at once, but also to measured that

exploitation and its effects negative effects. However human

beings are just standing by, without any signifit question or abguity

the about the

destruction of the Earth's biosystem and they are doing nothing to

prevent or shield it from collapse. We are unable to take

contorl as the global processes of deforestation, desertification,

pollution, climate change, and the rapid extinction of species appear

before us. Just how long will human beings as a whole will stand

by and bear witness to this distruction and ultmately the extinction

of the human species is

unclear, because you must ask what were they thinking when they cut the

last gaient palm tree leading to not only the extinction of that

species of tree, but also the extinction of people of the easter island

on which their survival depended. The enviromental history of earth provides

unrefutable proof that indeed irrational thinking and inchoherent actions are the normal

behaviour for the human species and control over the negative

consumption

of the earth's resources and the distruction of biosphere on which we

all depend for survival is byond

the reach of mankind.

This dissertation could be viewed

and started out to be yet another study or more aptly put a bedtime

story with a happy ending of how once again the technology exists

that could be used

to save the human species from extinction

if only the human species were willing to be altursitic, but as the invesgation

continued it became clear that despite technology advances the human

species as a whole is totaly incapable of rational, choherent and

ethical behaviour needed to take the control of the global Enterprise

and man will cease to

exist. This dissertation has evloved into a study of the has become how humanity will be

transformed and enhanced by biodigital technologies and the emergence

of an alien form of life that is

unreconizable from its human orgians, except perhaps marked only by the

occocalsional lapses into inrrational inchoherent selfcentered ethics.

The dissertation concludes that extinction of the human species is a natural processes that can

be perhaps held back, but and as repugnet as it may be to some, can

not be avoided. Extinction

is not the failure of species, but

part of evloution. The tradagy would be the extinction of the human

species without its

successful evloution into another form of life.

Capitalism

as a dynamic, open system has gained

considerable traction

within the academic community, and perhaps the most compelling

arguments

in favour of this proposition are offered by Karl Marx's historical

materialism and Joseph Schumpeter's creative destruction. While both

foresaw that it was a dynamic

system were both new materials and

inovative efforts

persevere and eventually their emergent properties fuse and

re-combine in unpredictable ways leading to huge disruptions or bloody

revloutions in the

established social, political, and economic spheres. Marx came to relise the supremic of

materials and processes from a historical view point and focused

on issues of communal ownership that came under instutlized centrial

contorl. Shumpeter argued that the precursor of creative

destruction will take place in

the form of increased

institutionalisation, which effectively reduces the search for

disruptive innovation to routinised incrementalism that stifles

innovation. Thus perdictes

both the self distruction of large centrelized instutions be it

communisum which in fact has suddently collapsed under the pressures

of a negative

form of capitalism called globlization that was more inovative and dynamic. Globlizaion

globaly inforced by the World Trade Orgnization (WTO) is its self

a

centrelized system that not only seeks increased institutionalisation

forcing open local markets and finical systems a process thus called "free market Capitalism" for the benifit of the massive global

corp, but is also an irrational

system base on the unstainable consuption of global resrouces.

Therefore it must ether sef dictruct or to evolve in to a new

form of capitalism based on more rational values based on fact

including the quality of the local and global enviromental

conditions.

In this dissertation we invesegate the

historical observations of Max concerning the supeoritor of materials

and processes and pay homage to shumpeter's regognization that the

forces of

This dissertation based on the premises that the natural world is finite, dynamic and that physical and biological determinants limit the range of options available for the evolution of capitalism into new forms of social structures. The dissertation invesgates the physical determinants of digital materials and processes in relationship to the biological limits of our enviroment to reveal the various forms of social structures that capitalism can evolve into. The dissertation will show that the next evolutionary step of capitalism rather than revolutionary will produce new organizational structures that only have their parallels in bioitc growth are so changed that they will be easly charized, defined and measured. We will for the purposes of this dissertation call these new higly effecent and inovative emergent micro bioitc organizations Organis. Given the dissertations premise we will successfuly argue that the Organis structures emerge from the nature of the superior qualityies of digial materials. These qualities include dimensionaly, speed, chorency, intergrealty and implicit generality. Accordeling we hold that in the digital age of information the soical mores of oppenness, transparence of tranactions, and accountalbity will be based on the ethics of digital animisum as expressed in digital freedom of information and devices, human rights and enviromental sustainable the three provisions of the Common Good Public License agreement. http://cgpl.org

that provide n-dimensional space for the creation of

virtural objects with all of their possible physical static and dynamic

properties; the speed of light for their transmisition and quantom

speeds for their modification and interactive enhances human

beings unique abilities to accumulate, process and share factual

knowledge and to form accurate knowledge of the structure and limits of

the biosystem of the space craft

Human

beings are in a unique and fortunate position among all living things

in that they have language, memory, and intelligence. These abilities

allow them to accumulate factual knowledge. And this knowledge, in

turn, makes it possible for them to break out the patterns of behavior

normally determined by habit, culture, religion, and genetic endowment.

When knowledge of the structure and limits of the Earth's biosystem is

gained and acted on, it can lead people to live as sustaining members

of the Earth's biotic community. People can maintain a limited, stable

population; they can minimize their use of physical and biological

resources. There is, however, no assurance that people will allow

ecological knowledge to direct their moral behavior rather than let it

be controlled by a priori assumptions or appeals to habit and

tradition. Nevertheless the challenging possibility exists: moral

behavior can avoid the tragedy of the commons even while it is

directed, secondarily, to the task of steadily improving the quality of

human life.

that

the next evolutionary step of capitalism

rather than revolutionary will produce new organizational structures so

changed in their nature that

they will be easly charized and measured. We

will for the purposes of this dissertation call these new higly

effecent and inovative mergent micro organizations Organis. 1.

Organis socal structures will emerge from the nature of the superior

qualityies of digial materials and processe that include

n-dimensionaly, speed, chorency intergrealty and implicit

generality. The soical mores of oppenness, transparence of

tranactions, inovation and accountalbity of these orgnizations will

be based on the ethics of

digital animisum as expressed in digital freedom of information and

devices, human rights and

enviromental sustainable the three provisions of the Common Good Public

License agreement. http://cgpl.org

Based on the premise that current disruptions in the music industry caused by online distribution channels, digital formats (ie. MP3), decentralised technologies known as Peer-to-Peer (P2P), and changing consumer preferences, are most likely to infiltrate other realms of society and economy, this dissertation proposes to investigate first,

The dissertation proposes to investigate:

first, if a set of novel consumption, production and intersecting collaboration patterns premised on massive decentralisation of resources, and capable of functioning without the oversight of central governance or institution, that the author defines as P2P, is indeed the modern expression of the process of creative destruction that Schumpeter envisioned as being the defining feature of capitalism;

[1] if a set of novel consumption, production and intersecting collaboration patterns premised on massive decentralisation of resources, and capable of functioning without the oversight of central governance or institution, that the author defines as P2P, is indeed the modern expression of Shumpeter's process of creative destruction; second,

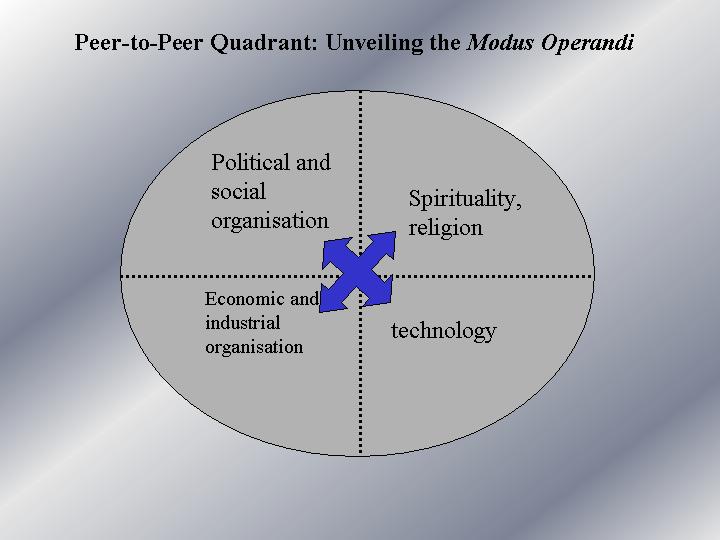

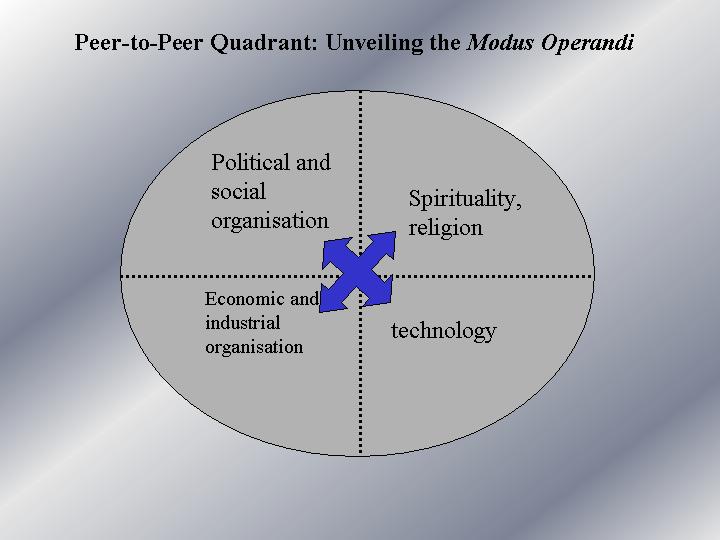

second, to test the practical usefulness and theoretical robustness of the proposed theoretical framework consisting of four quadrants, which will be employed in the course of the research to analyse the extent of creative disruption at work in society and economy;

[2] to test the practical usefulness and theoretical robustness of a proposed framework consisting of four quadrants, which will be employed in the course of the research to analyse the extent of creative disruption at work in society and economy; and third,

and third, to determine which forces and factors will accelerate or slow down this process of creative destruction.

[3] in retrospect, to determine if the disruptions in the music industry are indeed poised to extend to other cutural, economic and socio-political spheres, and consequently which forces and factors will accelerate or slow down this process. To this objective, the findings from the analysis of the music industry will be complemented and compared against the findings from additional case studies, such as the telecoms and software industry.

Academic Importance and Relevance to Social Science

The dissertation is important for a number of reasons. Despite the fact that capitalism has been thoroughly researched and analysed both as a social and economic system, consensus as to whether capitalism is static or not, and whether its properties are continuously changing or not, has not been reached. Not only this, but contemporary conceptions of capitalism differ enormously in scope, perspective and narrative. Indicatively, LSE 's John Gray regards capitalism as inherently evil, and attributes all social ills to capitalism's relentless drive to control the pace of life and work on a global scale. Cambridge's Noreena Hertz claims that global capitalism reflects the end of democracy, and renowed political analyst Francis Fukuyama asserts that capitalism is a suffocating blanket of sterile cultural homogenisation, and political paralysis. On the other hand, Thomas Friedman, Charles Handy, and even the world wide known financial markets speculator George Soros argue that capitalism may seemingly rest on several identical principles, but at the end of the day capitalism is an evolving system shaped by many factors, including but not restricted to spirituality, civil society, technology, public policy, and people's needs and desires. Against this background, the need for additional research is obvious, especially when considering that in much the same way that our world progressed from feudal to information – based societies and economies, there are imminent signs of a similar transformation toward an unfolding socio-economic arrangement where the dichotomy between consumption and production tends to blur, and access to a massively decentralised pool of resources is more important than central ownership and control of those very same resources. This new paradigm that I have coined Peer-to-Peer for the purpose of this dissertation holds many interesting lessons for the organisation of society and economy, as it proposes novel socio-economic processes and structures. Yet, peer-to-peer is fraught with a layer of ambiguity, and as such, it needs to be better conceptualised. This conceptualisation, in my opinion, can be advanced through the association with the process of creative destruction that Joseph Schumpeter envisioned about sixty years ago.

In retrospect, through this association, Schumpeter's theory of creative destruction will be critically examined and we will finally come to understand if creative destruction is a mere theoretical construct that bears no relevance to the real-world, or if the socio-economic discontinuities that are now coming into shape are indeed what Shumpeter described as the creative destruction of capitalism. Schumpeter offered that innovation is the defining feature of capitalism, and the glue that holds its properties together. So, it would be easy to assume that any innovative activity indicates a presence of creative destruction. For all its attractiveness, such an assumption is flawed. This dissertation goes further than that, and does not fall prey to such cognitive errors stemming from over-inflated excitement. The only innovation that will be considered as an indication or ongoing development of creative destruction will be the innovation that 'changes the rules' of the game by displacing dominant mindsets, established structures and processes, in effect resulting to new socio-economic structures and new modes of organisation in society and economy alike.

Consequently, the dissertation is of interest to several closely related fields of social science. For example, in the space of the research, several online communities will be observed and researched, and this is related to the field of socio-cultural anthropology. Indeed, a whole new sociological field – that many refer to as cyber anthropology or anthropology of the digital society - has recently emerged which is concerned with the analysis of online social networks, and how the Internet affects community life in large. And communities, as diverse as the Napster music sharing community, the counter-globalisation community, and the Open Source sofware producing community, are found in the epicentre of the dissertation.

More elaborately, the dissertation concentrates on the organisation of the emerging model of society, a model so complex that cannot be understood by means of economic analysis alone. That is partly because technology is increasingly pervading our lifes, setting the tone for our daily interactions, consumer preferences, and influencing our collective perception of what constitutes a post-modern social system. But technology alone neither changes anything, nor can it be properly explained with solely economic constructs. Unless technology finds a social vacuum where it can cultivate its distinctive properties, merge and fuse with other socio-economic artefacts, the stage is not set for any major discontinuities. And the sociological approach is the best instrument at hand in order to work out the interactions between technology, economics, and history, and understand whether an economic trend is more than a red herring.

Economics and political science are also closely related to the theme of the dissertation. Social science has long been interested in how society and politics adapt to economic forces and how the economy is affected by socio-political changes. Capitalism, or any other socio-economic system for that matter, is not an exception. And above all things, this dissertation sets to analyse how capitalism evolves and if the curret evolution can be understood through an association with the sphere of tehnology and the socio-economic relations that the latter brings into force. For instance, as new technology makes new organisational structures possible and more cost-effective, political organisations adopt these new structures to take advantage of switching costs, and in the process the face of socio-political structures changes too. Therefore, the same lessons that hold true for business organisations may hold true for political organisations too, and the proposed analytical framework is flexible and inclusive enough to detect and critically examine if disturbances in one sphere are likely to infiltrate another. The point I am trying to raise here is that the economy and the society are not separated, and any wel-designed analysis should carefully consider their interdepencies. Following the tradition of the Shumpeterian approach, this dissertation encourages the integration of sociological understanding into economic theory.

Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter (1943) asserted that capitalism will inevitably reach a stage of self-destruction as a virtuous circle of learning and self-evaluation, which takes place within the institutional periphery of the system, will ensure the routinisation and institutionalisation of the previously autonomous enterpreneurial function. The enterpeuneur will be supplanted by institutions, and innovation – the driving force of economic growth – will be reduced to mere routine. More specifically, capitalism, if treated as a civilisation, constatly enlarges the social space within which rational decision-making applies, said Schumpeter. And this very fact suggests that capitalism will eventually learn how to replace the human carrier of innovation – the entrepreneur – with institutions that carry out the same functions, including social leadership. For all its advantages, such a system obviously values stability and incrementalism before discontinous change and disruptive innovation. The reason is twofold: first, inescapable bureaucracy creeps in the system due to large scale routinisation and dehumanisation of work. Second and most importantly, innovation is a domain excempt from rational decision-making (Bower and Christnensen 1995, Rosenberg 1994, Schumpeter 1939; 1943), hence the engines of creation of disruptive innovation and thus of discontinuous change are not likely to be favoured by such a high level of institutionalised control.

Such a system of controlled incrementalism cannot remain stable forever and, as a matter of fact it is itself generating conflict internally in its struggle to manipulate the global barometer of geopolitics (Friedman 2000, Toner 2003), as well as exert control over potentially revolutionary applications of science and technology. The system is susceptible to pressures from within that become increasingly more evident as technology matures to respond to blurred and ill-defined socio-economic needs, as well as when technology fixes are aimed at re-adjusting previously given political, economic and legal equilibria. Perhaps this might come across as another argument in support of technological determinism, but it is not. The dissertation draws upon Schumpeter's insight that innovation is an activity endogenous to capitalism in the sense that economic forces lying at the core of capitalism play a decisive role upon the uses any given technology will be put into. Some times, as was initially the case with the telephone, the laser and the radio, economic actors, technologists, innovators and inventors alike fail to see how an innovation may be of any social, commercial or political significance (Rosenberg 1995). In those few cases, the innovation in concern reaches the hands of mainstream users who put it into quite different uses than those expected by its developers or commercial managers. By the time this becomes obvious, and given that the innovation is likely to disrupt existing markets and revenue models, economic forces join the race to ensure that the innovation is either killed, commercially exploited exactly because of being disruptive, or incorporated into existing business models as an improvement or complement to already existent products, services and processes (Bower and Christensen 1995).

Peer-to-Peer (P2P) is such an innovation. More accurately, Peer-to-Peer is a technological domain galvanised by intense innovative activity, and different economic forces at play have been approaching it in different ways. Interestingly enough, the industries now most affected by it are going to extreme pains to kill it right off the ground before it unveils its full potential.

A Case of Creative Destruction: Music Wars

Consider the case of the music industry: a few years ago, Napster, a Peer-to-Peer innovation, revolutionalised the music industry by empowering people to share their privately owned music with others. The industry responded with legal action and finally succeeded in bringing Napster to its knees. In parallel, due to widespread fear of legal litigiation, colleges and universities worldwide sought to restrict access to such Internet-accessible services, and conditioned students with expulsion. Despite all this, a swathe of Napster-like clones sprung up, and the industry now resorted to bringing legal slander against individual users, if its actions against Napster-clones proved insufficient. Fact of the matter is that the value chain of the music industry is bound to undergo a major reconfiguration (Mansell 1997, May and Singer 2001, Dolfsma 1999; 2000). Still, it resists change and it fights against what could be seen as a new source of innovation, both in terms of process, product and organisation. Napster and similarly functioning software like Freenet, Gnutella, AudioGalaxy, and Kazaa demonstrated clearly that users want to redefine consumption as an essentially peer activity (Oram et al. 2001, Leadbeater 2002) and that innovation by the end users is possible (von Hippel 2001, 2002, 2003) in a post-industrial world where products are continuously updated and highly customised to suit individualised preferences (Stark and Neff 2003).

The case of the music wars is a perfect example of creative destruction, whose consequences cannot be foretold. First, whether the advantage of having an established reputation as a record company will persist remains to be seen. Other advantages – in terms of organisation, distribution, and economies in production- have diminished. According to Teece (1986: 285-305), the parties that innovate are, when demand is fluctuating strongly, more likely to benefit from their creative efforts. In this environment, product innovations precede process innovations, giving the firm who first introduces a new product and draws the market’s attention to it, a considerable head start. A look at MP3 players justifies it, as 90% of all MP3 players are manufactured by unknown firms. Second, and this also relates to the unforeseen impact of creative destruction, digital technologies like Napster and MP3 can be used to boost the sale of MP3 players, but on a different level they can also be used to eliminate environmental hazards steming from the disposal of material goods like vinyls, and CDs.

Napster was a disruptive-sustaining technology hybrid that sought to address an unknown but real market need. Still, the music industry refuses to recognise the very existence of the market demand for downloadable music in digital formats that produces new socio-cultural arrangements and usage (consumption) patterns. It still remains to be seen what will be the end of the so-called music wars, but it is very likely that Napster-like software will persevere, although its usage could be criminalised and its users marginalised. Nevertheless, the music industry and its struggles is not an exception, but rather the norm.

Yet Another Example of Creative Destruction: Enter the Telecoms Industry

Another case where peer-to-peer is leading to an avalanche of industry transformations is illustrated by the telecoms' love-and-hate relationship with peer-to-peer. Initially, the telecoms sector hailed peer-to-peer as the future of mobile communications and incorporated it into their business models. It should be noted that what first ignited this enthusiasm in peer-to-peer is the huge success of text-messaging (SMS) on mobile phones. Text-messaging is one of those applications whose success was not anticipated. None expected that mainstream users would be so fond of text messaging, and that text-messaging would become a cash-cow, culminating into a trend among the younger population of users. Widespread optimism surrounding peer-to-peer still persists, and the current explosion of multimedia messaging services (MMS) on mobile phones is the continuation of the same trend. Ovum, a leading consultancy in the area, advocates that peer-to-peer is clearly the future” (Ovum 2001) and that “peer-to-peer drives growth” (Ovum 2002) since people demonstrably like to exchange photos. Superficially, and insofar as peer-to-peer is about exchanging photos (the first popular application of MMS), the structural and competitive dynamics of the sector seem unaffected. From that angle, peer-to-peer is not a threat to existing business models and industry structures. It goes without saying that several minor changes in pricing models and marketing strategies had (have) to be introduced in order to appreciate the additional revenue that text-messaging then and multimedia messaging now promises, but that is hardly a shock that market leaders cannot absurb. On the contrary, it is a huge opportunity that telecoms are quick to seize without having to agonise over unexpected competition from smaller players.

But the future is much more blurred. Multimedia messaging, we should bear in mind, is only the first emerging example of peer-to-peer entering the world of telecoms. According to the same industry experts that praise the growth potential of peer-to-peer, and urge telecoms to focus on MMS now, the future is bound to be unsettling, at least for those that rest on their laurels. Soon, exchanging static photos will not be a reason compelling enough for most users to jump on mobile telephony, and technology is not going to prevent them from asking more. In fact, peer-to-peer technology will unleash a whole new range of possibilities, that we have just started to catch a glimpse of. This new range of possibilities is coming into full force under the banner of pervasive/ubiquitous computing. Despite the confusion that the term invokes, its effect is poised to result in a creative destruction of the telecoms sector. Pervasive/ubiquitous computing is about an ideal: “any information service to any device over any network” (Ovum 2001). People will use their phone to communicate with their home appliances and with remore networks in a peer-to-peer fashion. A user will instruct (will phone) his home air conditioner to raise the bedroom temperature to 25 degrees C, so that when he gets back from work, he and his wife will be able to enjoy the warmth without having to pay a huge electricity bill that would have been the norm had they no other alternative than setting the air conditioner to that temperature from the very morning they left the house. Or a journalist on a night-shift will instruct (will phone) her VCR to record a night-show on her home TV set in order to watch it later the next day when she comes home. This fusion of telephone and computer and other appliances is usually referred to as digital convergence. Scores of users are already using their technologically enhanced phones to upload and post files to their websites, to connect with remote computers and networks, to receive information about the stockmarket, the weather, or good restaurants in their viccinity, and this only the begininning.

So, you may wonder, why is this an example of creative destruction? First, because in this case peer-to-peer opens the door for many more actors, and shatters rigid pricing models. Platform operators will no longer be able to control the information users send and receive, and the likelihood of many small competitors entering the telecoms arena to provide all sorts of new services is great. It is a safe speculation to assume that Internet Service Providers (ISPs) will be the first to seize this opportunity. All this renders current pricing models and industry structures inappropriate to handle the mounting complexity. Indeed, it is expected that the balkanisation of the space is imminent as content providers, platform owners, and network-infrastructure operators will each seek to capture a fair share of the rapidly emerging market. The current consolidation in the space is the first development underway, reports the Economist (2002), and points to further radical developments as telecoms will have to re-think their strategies in the face of skyrocketing, yet realistic, consumer expectations. As mobile devices are becoming Internet-enabled by having been assigned an IP address, the essence of a fairly-priced phone call changes dramatically.On the Internet, you are not been charged by the amount of emails you have sent or received, so why should you when using any other Internet-enabled device for that matter? To counter this problem, most operators of third-generation wireless networks have revised their pricing models so that any third-genartion mobile phone will be constantly and permanently connected online, and users will be charged according to how much information they receive. However, a more realistic problem is fragmentation due to incompatible, closed, proprietary networks and standards, as is now the case with US, European and Asian networks and platforms, and this invariably hinders progress in the space and will lead to further competitive battles.

But lets' return back to the present reality. As said, peer-to-peer and creative destrcution change the rules of the game. While telecoms find it very hard to co-operate and agree on commonly shared open standards, the threats to their business model multiply, and Skype – a P2P telephony platform that can be used for free - has gone mainstream in Estonia in less that a year. Consider the example of Estonia, a country struggling to leapfrog into the information age. In Estonia, Skype has crossed the chasm to the mainstream market in double-quick time, and now enjoys widesptread adoption by Estonians. As Ross Mayfield (2003), former advisor to the President of Estonia, says:

“When something big happens in a little country, word gets around fast. Even my father-in-law is using Skype to call us (instead of our Vonage line). Family doctors are using it to set appointments and communicate with patients. I don't have any country-by-country statistics (do you?), just personal anecdotes that regular people are using Skype in droves instead of calls. People are using it for more than saving money with call quality above standard (better than mobile) -- but because the mode of use differs it is gaining a different culture of use.”

So, all an Estonian needs to make a phone call overseas at marginal cost, is a computer with a connection to the Internet, and Skype. Duration of the phone call and geography no longer matter. And the spectrum of services that Skype offers is expanding fast. Soon, one will be able to receive “Skype calls” on a mobile phone and landline, and on other devices as well. The telecoms sector should better start thinking hard about where their competitor may come from, and how the industry will be re-configured with the entrance of players exploiting peer-to-peer like Skype.

Nevertheless, this does not mean that institutional pressures are nowhere to be seen. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has been discussing ways to introduce a layer of regulation to VoIP (voice over Internet protocol), and Skype is not excempt from FCC's plans (McCullag 2003).

Massive Turmoil and Institutionalisation

Some of the cases at hand whose long term evolution is more dependent upon institutional pressures, rather than market forces and consumer behaviour, include the provision of complex public goods like public transport; health services that are increasingly seen as irrelevant to the actual needs of patients; free and open source software that represents a threat for dominant market players and as such it ought to be controlled; information and cyberspace in large which is always at the epicentre of legal battles fought over intellectual property (IP) concerns; regulated telecommunications that opened some space for small players like Internet Servive Providers on the pretext of harnessing competition while failing to address more serious issues such as preventing incompatibility among platform providers for mobile telephony in Europe, Asia and America; biotechnology and its love and hate relationship with patents and IP law; molecular manufacturing – nanotech; the sequencing of the human genome and the ethics of who owns your DNA; genetically modified food's inseparable dystopic and utopic premise made known through the rise and fall of Monsanto; the potential payoff of alternative sources of energy hindered by the Enrons of the world; bottom-up micro-media and independent publishing patronised by media conglomerates and marginalised as a result of media concentration; and so many many others. It is not my intent to demonstrate that the situation is now worse or better off when compared to some earlier epoch. This is not a question of pessimism or optimism, personal stances and beliefs notwithstanding. All I mean to draw attention to is the widespread turmoil that pervades the spheres of creative arts and culture, science and technology, politics and business. As if creative destruction is behind the scenes, eagerly waiting for its chance to deconstruct myriads of industry value chains, and re-program people's needs and desires.

The issue in concern is that enhanced institutionalisation is evident across scores of industries. The World Trade Organization (WTO) dominates discussions and agreements over trade, information, and all sorts of property rights including intellectual property; the Recording Industry's Association of America (RIAA) has consolidated the production and distribution rights of music producers and content onwers and forcefully asserts its legitimacy over music users; the Moving Pictures Association of America (MPAA) does more or less the same with movie products; and potilical artefacts of modern capitalism such as copyrights and patents (May 2003) have become global, uniform, and ever-pervasive. It is not that institutional bodies are necessarily harmful. In plenty of cases, institutions can be highly beneficial if their governance model is not authoritative, allows the highest level of participation, and their goals do not contradict social and economic welfare, and do not stifle veins of creativity and innovation that enrich the public realm. But again, this is not a discussion about whether institutions' existence is for good or ill; the inefutable truth is that institutionalisation has severly increased during the last fifty years. And this is a sign, a possible indication if you prefer, of the impending creative destruction that Schumpeter envisioned.

But what is less obvious is the form of expression, as well as the fueling source of the creative destruction. Put bluntly, creative destruction is a vague theorem that bears no resemblance to ongoing socio-economic developments. It needs to be further conceptualised, as well as undestood with reference to present technologies, social functions, organisational traits, and economic trends. This dissertation proposes to analyse and examine this creative destruction by association with a framework of overlapping and interconnected concepts, which have been commonly referred to as peer-to-peer.

P2P can be very broadly defined as a set of technologies and principles of organisation (that are facilitated by underlying technologies) that allow symmetries of information, co-ordination, communication, collaboration, distribution and exchange. Unfortunately, there is no single definition and the term P2P carries many connotations (Oram et al. 2001). For example, many regard the telephone as P2P, as well as email, instant messaging (IM), USENET, the original architecture of the Internet and the World Wide Web (WWW) (Ibid.). Others extend this concept to encompass spirituality (Bauwens 2001), production-consumption (Bauwens 2001, Oram et al. 2001), politics and social organisation (Bauwens 2001, Ito 2003, Moore 2003, Rushkoff 2003). In the context of the proposed dissertation, P2P is defined as a set of novel consumption, production and intersecting collaboration patterns premised on massive decentralisation of resources, and capable of functioning without the oversight of any central governance or institution.

2. Making Sense of Peer-to-Peer

As previously said, P2P is a term fraught with confusion and open to wide interpretation. So, let's try to put it into a perspective that will further our understanding, and enable us to reach a useful framework of analysis. First, P2P consists of a strong technological element. Indeed, it can be argued that regardless of which sphere of influence the framework focuses upon at any given point during the analysis, technology will be of central importance as it is this element that provides the underlying platform upon which novel consumption, production and collaboration patterns unfold. Hence, technology is one of the aspects, but its role is merely facilitatory. Put otherwise, the presence of P2P technology alone will not be sufficient evidence of disruption of current structures, but its adoption and various real-world implementations in other spheres is likely to give birth to discontinuous change.

“P2P is also a strong challenge to both established and new religions which more often than not are based on the organisational forms that existed at the moment of their birth. These feudal formats and doctrinal forms have been challenged in works on the 'peer to peer turn' in spirituality, in works by John Heron (sacred and cooperative inquiry), Jorge Ferrer ('the participative turn in transpersonal psychology') and others, and in the creation of a multitude of peer to peer circles concerned with the spiritual search”.

Of course, researching all religions, spiritual circles and sects is a daunting task, both due to the complexity inherent in analysing religious organisations and the sensitive nature of spirituality. I do not propose to do this. Although Schumpeter intentionally downplayed the role of this domain in his classic analysis of capitalism, it goes without saying that a creative destruction in the realm of politics and business would inevitably be paralleled by a creative destruction in the realm that sustains and reinforces the supremacy of both worlds of politics and business. Throughout history, huge distrubances in the social, commercial and political realm were always accompanied by changes in the religious and spiritual domain. Evidently, in the aftermath of the collapse of the Roman Empire a loosely-coupled network of believers in Christianism emerged and took over the reigns of power. This counter-empire used no military might; it resorted to forging strong peer-to-peer networks built on Christian values that survived the decadence of the Roman Empire (Bauwens 2001, Negri and Hardst 2001). The October Revolution in Russia, which changed radically people's perceptions of religion and spirituality, points to similar conclusions, although the use of state endorsed propaganda was in this case employed to “topple the previous spiritual establishment”. And this is a very powerful argument to ignore.

Nonetheless, one may wonder how those discontinutities will be diagnosed and explored in connection with our analytical framework. Here, the presence of a high level of technology intervention in a disruptive sense is one indication, as well as the tone, rhetoric, and orientation of the spiritual movement in question. For instance, the Catholic Church values stability, order and seeks to maintain some pre-existing status quo. On the contrary, a few scientific groups with spiritual extentions, or religious groups with scientific extentions, if you prefer, have duly started to emerge, such as the Singularitarians and Entropians, whose rhetoric is shaped by a fear in the path 21st century technologies are paving, but at the same time they hold a strong belief in technology for re-inventing their bio-forms and societies. Talk of several ways of defying death through technology is not uncommon in those circles (Bauwens 1996). And defiance of physical death through technology is a head-to-head challenge to the spiritual status quo. This dual co-existence of techno-utopia and techno-dystopia is a valid indicator of spiritual conflict as a forerunner of widespread social turmoil.

2.3 Social and Political Organisation

The third aspect of the framework is concerned with political and social organisation. Traditionally speaking, they are not necessarily parts of the same sphere, but in the context of this research they often overlap, and they will be treated as one. By saying that they don't belong to the same sphere, I do not mean they are irrelevant to each other; to this day they merely had different ends to achieve, and deployed different means. For example, NGOs (Non-profit organisations that are mostly sustained by volunteer labour and whose role is to cater for the interests of minority groups, special interest groups, and socially-critical causes such as Greenpeace) personify the civil society and seek to address imbalances that may stem from political errors. Yet NGOs have little in common with traditional political parties despite that they both seek to create a better world by voicing the interests of diverse stakeholders. This line of distinction though gets blurred when it comes to the counter-globalisation (anti-globalisation) movement.

Are the anti-globalisation campaigners political activists or social scene organisers? Are they representing a global constituency that no political party has yet managed to tap into? Or are they disgruntled civilians with no interest in politics whatsoever? As far as I am concerned, there is no easy answer, and this dissertation does not make the claim that it wil suggest a dichotomy between social and political organisation. The anti-globalisation movement is both a social and political phenomenon. Leaderless, empowered by technology and organised in a massively decentralised fashion that allows no time slack for elaborately hierarchic responses to occur, anti-globalisation campaigners have effectively infiltrated venues of political discourse and continue to mobilise resources to their goals primarily via independent media centres such as Indymedia, email and mobile phones. It could be safely argued that the anti-globalisation movement is a solid example of a social/political movement organised in a peer-to-peer fashion (Bauwens 2001).

Others like academic Siva Vaidhyanathan (2003a, 2003b) believe that peer-to-peer as a template of social and political organisation presents a growing challenge to the nation-state, and unveils the promise of a borderless global landscape where bottom-up cultural expression blossoms and forms diasporic communitties. The premise that P2P technologies will lead to some re-invented modern cultural, scientific, and ultimately political rennaissance pervades his work. Based on the observation that culture has been repeatedly exploited by political punters as an antitode to destabilising social currents (Arnold 1932, Huntington 2002), he proclaims that P2P will ultimately lead to some form of socio-cultural anarchy as culture will no longer be dominated by media monopolies, or moulded by centralised cultural priesthoods.

In a similar vein, Joichi Ito (2003) and James Moore (2003) have convincingly argued that a higher state of democratic consciousness can only be realised through peer-to-peer structures, that in turn are made possible through the decentralised use of online peer-to-peer collaboration, communication and publishing tools, usually referred to as weblogs, and current US presidential candidate Howard Dean seems to have taken their recommendations very seriously since he started campaigning and conversing with his followers online at his weblog tentatively entitled Blog of America at http://www.blogforamerica.com The New York Times concludes that what Dean's actually doing, and he is doing it very well, is to install a collaborative infrastructure at the centre of his campaign which is not controlled by the top; instead, it feeds off of the nodes at the edges of the network – the volunteers who are being empowered to act without asking for permission from the centre – and this certainly maximises the efficiency of a campaign run by a political outsider (Shapiro 2003). In a Washington Post article, former US undersecretary of commerce, Everett Ehrlich (2003) agrees that Dean's decentralised model of campaign shuns any requirements for centrally-run political machines and unveils the organisational structure of political organisations to come. Joichi Ito, a Japan-based venture capitalist involved in several law bodies like Creative Commons, and James Moore, a Harvard Law School scholar, have a good grasp of how representative democracy works, and their argument does not fall prey to over-the-top pitches and cries for social revolutions. They believe the transition will be silent as those online tools enable the masses to influence mass media, which effectively gives the power to otherwise powerless individuals to draw public attention to issues that have evaded the mainstream media. And as the case of Trent Lott demonstrates, whose racist comments during Strom Thurmond's 100th birthday party were briefly, if at all, covered by the media, but upon the persistence of weblogs the mass media world was compelled to give it the coverage it deserved, their argument is not lacking substance in contemporary politics (Noah 2003).

It should be noted that weblogs do not enable the formation of social and political networks modelled on P2P by means of technology infrastructure alone; rather, they create the necessay preconditions for a P2P social and political organisation because weblogs blur consumption with production. Webloggers are independent content producers as well as content consumers facilitated by technology. As Dave Winer (2000) puts it, and in this case he is incredibly right, the P in P2P is about people.

2.4 Economic and Industrial Organisation

This is obviously the most crucial component of the framework, and perhaps the most easy to be analysed. Here, creative destruction is synonymous with massive industry turmoil of the type experienced my market incumbents in the music industry who try to kill a distribution channel that music consumers seemingly prefer to traditional distribution models, and with emergent forms of industrial organisation, a succinct example of which is the paradigm shift represented by the development and governance model typically found in free/open source software projects like the Linux operating system and the Perl programming language.

Why is it a paradigm shift? Well, the dominant model of industrial organisation is the large firm in its various configurations (dividionalised structure, conglomerate, multinational, matrix, etc.), which is premised on strictly-adhered guidelines, hierarchic structures, and direct monetary returns for employees. In total contrast, free/open source software is developed in a massively decentralised fashion by volunteers, with no respect to deadlines, organisational charts, and common yardsticks of engineering success, and decisions are made in the open and based on solid technical grounds rather than personal status. In addition, free/open source software is given away for free. Yet, despite this unorthodox model, the free/open source software community has managed to produce first-class software in a fragment of the time and resources that conventional software companies invest in order to produce something of comparable value. For instance, the Linux operating system, which is clearly superior to any Microsoft offerings, is the product of ten years of volunteer labour by thousands of globally dispersed individuals (Dafermos 2001). And although it goes largely unknown, all the critical infrastructure of the Internet (DNS, Bind, Sendmail, TCP/IP) and the WWW (HTTP, HTML, XML) is free/open source software. Needless to say, business models based on free/open source software do exist, but they differ enormously to the industry norm and as such, they are disruptive to the prevalent revenue model of most commercial software companies. This is no doubt a sign of creative destruction in action.

Methodological Framework and Data Collection

The research is qualittative in type due to the long tradition in the social and organisational research field to undertake a qualitative approach when analysing organisational trends and changing paradigms (Etzioni 1969). It is my hope that the findings produced by this dissertation will be cross-examined and complemented by quantitative reseach in the future.

Personal in-depth semi-structured interviews

The primary research component of the dissertation will adopt a thorough multi-dimensional perspective, comprising dozens of personal in-depth semi-structured interviews with key figures. Those key figures are the authors of key texts with regard to the scope of analysis such as Michel Bawuens, Joichi Ito, Siva Vaidhyanathan, and Douglas Rushkoff, and leading P2P technologists involved in reshaping the technology landscape like Reto Bachmann-Gmuer, Paul Boehm, and Jo Walsh. It should be noted that I have already secured access to the above mentioned individuals, and I believe I will encounter no problems in my effort to secure access to more key individuals due to my long-time involvement in technology circles. Semi-structured interviews can produce both qualitative and quantitative data (Crozier 1964), but the reason we chose this form of interviewing was in order to make the interview pleasing to the persons interviewed. Also, semi-structured interviews provide rich detailed data of greater value than straight question and answer sessions especially when the research aim is to explore a phenomenon (Zweig 1948). Moreover, they do not put the interviewer in an unnatural relationship with those who are researched (Roberts 1981). Overall, field researchers use a semi-structured (or unstructured) approach that is based on developing conversations with informants and this strategy follows a long tradition in social research where interviews have been perceived as 'conversations with a purpose'. They are usually used to complement observation and other techniques and they achieve the flexibility needed when dealing with a complex phenomenon (Finch 1984).

In addition, observation and participation in key scientific communities (global communities whose raison d'etre and reseach orientation is closely aligned to the theme of this dissertation – P2P with respect to society and economy - like the Extropy Institute, the Oekonux Project community, and the Free/Open Source Software community in large) will be critical in shaping our progress by means of triangulating existing data, testing out our hypotheses in the real world, and providing us with a unique research perspective. Thereby, such research communities are also part of the reseach analysis. For example, the free/open source community, which is a critical actor in the software industry, is an assemblage of many smaller research communities all of which shape and are shaped by the premise and the findings produced by the dissertation. These research communities are the best likely sources with regard to identifying suitable case studies. To clarify things, for instance the Extropy Institute is the world-leading producer of scientific research and hands-on experimentation on the socio-economic implications of nanotechnology and molecular manufacturing (indeed, scientific realms embodying the P2P principles as defined by the scope of this dissertation) and their knowledge will be instrumental in allowing us to understand which industries and sectors are more susceptible to creative destruction. These communities of researchers and practitioners will point us to appropriate case studies, which will be further researched. As of the time of writing this proposal, the case studies already identified are the software industry, the music industry, the telecoms industry, and the anti-globalisation movement.

Case studies allow in-depth understanding of the group or groups under study, and they yield descriptions of group events - processes often unsurpassed by any other research procedure. Also, and at a more pragmatic level, case studies can be relatively easy to carry out and they make for fascinating reading. But the real forte of the case study approach is its power to provide grist for the theoretician's mill, enabling the investigator to formulate hypotheses that set the stage for other research methods (Forsyth, 1990).

On the bibliographical side, a wide spectrum of works will be reviewed, a glimpse of which is available at the concluding section of this proposal entitled References. It is also useful to take a look at the following section - Literature Review - for a more elaborate discussion of the literature to be consulted in the formulation of our hypotheses.

Capitalism: Towards an Evolutionary Conception

For a good part of the last two centuries, social scientists have been pondering on the evolution of capitalism and scrutinising the likely terminal stage in its adoption on a global scale as the prevalent and omnipresent system of pervading social thought, modern economic history, and production activity.

To date though most analyses were doomed to fail since the dominant strand of neoclassical economics is based upon static frameworks, and the focal point in analyses of capitalism has mostly been about how the system restores stability. Characteristically, Francis Fukuyama (1993) foresaw the end of history, as most countries which have embraced a combination of free markets capitalism and liberal democracy reach an ultimum and irreversible state of social and economic stability, which in turn offers minimal incentives for morphing into less predictable and potentially less advantageous frames of governance. Fukuyama's claim is, of course, contradictory in terms of both structure, narrative, and character, and is above all flawed. Acclaimed economist Nathan Rosenberg whose work is focused on the intersections of economics, history and technology has repeatedly argued that capitalism principally depends upon its own capacity to try out uncertain alternatives with respect to technology, size and form of organisation. Had not been for these particular characteristrics, capitalism would have never strived, stipulates Rosenberg (1986, 1992, 1994) and with good reason. Furher, as leading UK business thinker Charles Handy (2002) stresses, implementations of capitalism differ across countries, say from India to America and from England to post-communist Russia. This exemplifies that capitalism, at least in the form that prevails today, is not a homogenising force, and thus offers a solid basis for refuting Fukuyama's thesis. Even Karl Marx's much disputed theory of historical materialism (1965) visualised capitalism as a transitional phase that would ultimately lead to socialism. Marx, writing more than a hundred years ago, grasped that capitalism is an evolutionary process.

Beyond the shadow of a doubt, the perception of capitalism as a dynamic system that continuously evolves has gained widespread popularity within academic circles, and this is further evidenced by the increasing popularity of what has become evolutionary economics. The father of evolutionary economics, Thornstein Veblen (1990) hints that both the free market search for perfect equilibrium and the communist obsession with control are but different versions of the same mistake. Nowadays, it is not rare to come across striking parallels between biology, computer science, sociology and economics. Concepts from the field of evolutionary biology, most notably the notions of adaptation, evolution, emergence, darwinian selection, and self-oprganisation have been successfully applied to the world of business strategy and economic policy time and over again (Axelrod and Cohen 1999, Dafermos 2001, Kauffman 1993, Kauffman 1995, March 1991, Stacey 1993, Stacey 1999). This has also led to the increasing popularity of economic and social applications of chaos theory and complexity science (Brian Arthur 1994, 1995, 1997, Johnson 2002, Pascale 2001). Or in a less straightforward fashion, economists like Paul Krugman (1996) offer that “economics would be a more productive field if economists learned something important from evolutionists: that models are metaphors, and that we should use them, not the other way around”. This trend in social science to explain socio-economic systems by referrence to chaos and complexity theory demonstrates clearly the extent to which the evolutionary perspective has progressed among academic circles.

Even though evolutionary economics has not entertained the catholic respect of economists for a long time, Joseph Schumpeter understood that “stationary capitalism is a contradiction in terms” (Schumpeter 1951: 158) more than sixty years ago, and argued that “capitalism...is by nature a form or method of economic change and not only never is but never can be stationary” (Schumpeter 1943: 82). According to Schumpeter, “the problem that is usually being visualised is how capitalism administers existing structures, whereas the relevant problem is how it creates and destroys them” (Ibid. p.84). The Schumpeterian approach, hence, examines capitalism as a form of economic change occuring through time, and the primary subject of investigation is how the economic system generates innovation time and over again.

Planning of Research and Publications

|

1st YEAR |

|---|

|

Review literature on innovation of evolutionary approaches and the Schumpeterian approach, evolutionary economics in large |

|

Review literature on peer-to-peer as a technology phenomenon, and in relation to the already identified case studies |

|

Review literature on the already identified case studies: music industry, software industry, counter-globalisation movement |

|

Design skeleton of dissertation, review skeleton, finalise design and start writing |

|

Produce questionnaire for personal, semi-structured, in-depth interviews and conduct a thorough pilot test |

|

Finalise design of questionnaire |

|

Analysis of preliminary qualitative data |

|

Attending and speaking at conferences, and publication of preliminary findings in conferences' proceedings, as well as one publication in an academic journal |

---- Milestone 1 ----

|

2nd YEAR |

|

Writing dissertation |

|

Conduct personal interviews |

|

Identify additional case studies |

|

Observation of and participation in communities related to the newly identified case studies and analysis of qualitative data |

|

Attending and speaking at conferences, and publication of preliminary findings in conferences' proceedings, as well as two publications in academic journals |

|

Peer-review/ Alpha Release submit an early version of the dissertation to research/scientifc communities related to the subject topic in order to receive and incorporate expert feedback |

---- Milestone 2 ----

|

3rd YEAR |

|---|

|

Writing dissertation |

|

Conduct additional personal interviews |

|

Observation of and participation in communities related to the newly identified case studies |

|

Analysis of qualitative data |

|

Incorporate additional data and conduct more interviews if needed |

|

Attending and speaking at conferences, and publication of preliminary findings in conferences' proceedings, as well as two publications in academic journals |

|

Peer-review/ Beta Release - Submit the almost finalised version of the dissertation to research/scientific communities related to the subject topic in order to receive and incorporate expert feedback. |

---- Milestone 3 ----

|

4th YEAR |

|---|

|

Final version (0.9) of the disertation completed |

|

Review |

|

Make any adjustments/modifications if needed |

|

Review |

|

Final version (1.0) of the dissertation submitted as requirement of the PhD |

|

Attending and speaking at conferences, and publication of findings in conferences' proceedings, as well as four publications in academic journals |

|

Submit final version of the dissertation to research/scientific communities related to the subject topic and publish dissertation |

2. Constraints to the Completion of the PhD

In all, I fail to see how the completion of the PhD could be derailed, unless the digital, social, and economic landscapes combined go through a process of radical restructuring that renders one-year old assumptions obsolete. Even in that extremely unlikely case, I propose to design the skeleton of the dissertation in a modular manner in order to reduce inter-dependencies among different parts of the dissertation. Given that the interfaces between different sections are well defined, this modular design of the dissertation will enable me to add or/and remove entire sections of the dissertation in a piecemeal fashion, in effect, making the revision and rewriting process much more easier and error-free.

Other than access to the University library, and supervisory guidance, no special resources are required, although I would appreciate it if I could be provided with a computer (I do not mind the architecture) with Internet capabilities and root/system operator privileges. If that is impossible, there is no problem, as I will have my own computers at home.

I expect that a number of papers will be published in academic journals, industry publications, and conference proceedings over the period of the doctorate assignment. I cannot foretell how many exactly these publications will be, but I expect that a minimum of one paper will be published in a peer-reviewed academic journal in the first year, two papers will be published in the second and third years, and four papers will be published in the final fourth year. It is my hope that the findings of the research will enrich the already existent knowledge on how capitalism evolves, and shed light on the new socio-economic arrangements fueled by the fascinating domain of peer-to-peer.

Matthew Arnold, Culture and Anarchy, Cambridge University Press, 1932.

Brian Arthur, "The End of Certainty in Economics," Talk delivered at the conference Einstein Meets Magritte, Free University of Brussels, 1994. Appeared in Einstein Meets Magritte, D. Aerts, J. Broekaert, E. Mathijs, eds. 1999, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Holland. Reprinted in The Biology of Business, J.H. Clippinger, ed., 1999, Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Brian Arthur, "Complexity in Economic and Financial Markets," Complexity, 1, 20-25, 1995.

Brian Arthur, "Process and Emergence in the Economy," introduction to the book The Economy as an Evolving Complex System II, edited by Arthur, Durlauf, and Lane, Addison Wesley, Reading, Mass, 1997.

Robert M. Axelrod and Michael D. Cohen, Harnessing Complexity: Organizational Implications of a Scientific Frontier. New York: Free Press, 1999.

Michel Bauwens, Peer-to-Peer: From technology to politics to a new civilization?, 2002. at http://noosphere.cc/peerToPeer.html

Michel Bauwens, Spirituality and Technology: Exploring the Relationship, First Monday, 1996. at http://www.firstmonday.dk/issues/issue5/bauwens/

Michel Bauwens, Peer-to-Peer, Integralism, Transhumanism: three challenges for the globalisation of religion, presentation delivered at the Globalization and Religion Conference, Institute for the Study of Religion and Culture, Payap University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, July, 2003. at http://religionandculture.com

J. L. Bower and C.M. Christensen, Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave, Harvard Business Review, January-February, 1995.

M. Crozier. The Bureaucratic Phenomenon. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964.

George N. Dafermos, Management and Virtual Decentralised Networks: the Linux Project, First Monday, November, 2001. at http://www.firstmonday.dk/issues/issue6_11/dafermos/

Wilfred Dolfsma. Valuing Pop music: institutions, values and economics, Delft: Eburon , 1999.

Wilfred Dolfsma. How will the music industry weather the Globalization storm?, First Monday, vol.5, no.5 (May), 2000.

Economist 2002, Watch this Airspace, June 20, at http://www.economist.com/printedition/displayStory.cfm?Story_ID=1176136

Everett Ehrlich, What will happen when a national poilitical machine can fit on a laptop?, Washington Post, December 14, Sunday, Page B01, 2003. at http://www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/wp-dyn/A58554-2003Dec12?language=printer

Jorge N. Ferrer and Richard Tarnas, Revisioning Transpersonal Theory: A Participatory Vision of Human Spirituality, State Univ of New York Pr, 2001.

J. Finch, "It's great to have someone to talk to": the ethics and politics of interviewing women," In: C. Bell and H. Roberts, (editors). Social Researching: Policies, Problems, Practice. London: Routledge, 1984.

Forsyth, D.R. Group Dynamics. Second edition. Pacific Grove, Calif.: Brooks/Cole, 1990.

Thomas L. Friedman, The Lexus and the Olive Tree: Understanding Globalisation, Anchor Books/Doubleday, 2000.

Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man, Penguin Books, 1993.

Michael H. Goldhaber, The Dean Campaign and the Internet, Nettime, December 11, 2003. at http://amsterdam.nettime.org/Lists-Archives/nettime-l-0312/msg00024.html

John Gray, False Dawn: the Delusions of Global Capitalism, Granta Books, 1998.

Charles Handy, The Elephant and the Flea, Arrow, 2002.

John Heron, Co-Operative Inquiry : Research into the Human Condition, Sage Publications, 1996.

Noreena Hertz, Silent Takeover: Global Capitalism and the Death of Democracy, Free Press, 2002.

Eric von Hippel and Nik Franke, Satisfying Heterogeneous User Needs via Innovation Toolkits: The Case of Apache Security Software, Research Policy, February, 2003.

Eric von Hippel, Horizontal innovation networks- by and for users, June, 2002. at

http://opensource.mit.edu/online_papers.php

Eric von Hippel, Open Source Shows the Way - Innovation By and For Users - No Manufacturer Required, March, 2001. at http://opensource.mit.edu/online_papers.php

Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, Free Press, 2002.

Joichi Ito, Emergent Democracy, 2003. at http://joi.ito.com/static/emergentdemocracy.html

Steven B. Johnson, Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants,Brains,Cities and Software, Penguin Books, 2002.

Stuart A. Kauffman, Escaping the Red Queen Effect, the McKinsey Quarterly, Number 1, pp.118-129, 1995.

Stuart A. Kauffman, The Origins of Order: Self-organization and Selection in Evolution. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Paul krugman, What economists can learn from evolutionary theorists, Talk given to the European Association for Evolutionary Political Economy, November, 1996.

at http://web.mit.edu/krugman/www/evolute.html

Charles Leadbeater, Up the Down Escalator: Why the Global Pessimists Are Wrong, Viking, 2002.

Charles Leadbeater, Living on Thin Air, Penguin Books, 2000.

Mansell, R. Strategies for maintaining market power in the face of rapidly changing technologies, Journal of Economic Issues, vol.31, no.4 (December), p.969-989, 1997.

Declan McCullagh, FCC to form working group on VoIP regulation, C/NET News.com, December 1, 2003. at http://rss.com.com/2100-7352_3-5112424.html

James .G. March, "Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning," Organization Science, volume 2, number 1, pp. 71-87, 1991.

Karl Marx and Engels, The German Ideology, London, 1965. (Written in 1845-6)

May, B. & Singer, M., Unchained Melody, McKinsey Quarterly, 2001.

Chris May, Digital Rights Management and the Collapse of Social Norms, First Monday, November, 2003. at http://firstmonday.dk/issues/issue8_11/may/index.html

Ross Mayfield, Skype Estonia, November 30, 2003. at http://ross.typepad.com/blog/2003/11/skype_estonia.html#comments

James Moore, The Second Superpower Rears its Beautiful Head, 2003. at http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/people/jmoore/secondsuperpower.html

Toni Negri and Michael Hardst, The Empire, Harvard University Press, 2001.

Shachtman Noah. Blogs Make the Headlines. Wired News, 2003. at http://www.wired.com/news/culture/0,1284,56978,00.html

Andy Oram et al., Peer-to-Peer: Harnessing the Power of Disruptive Technologies, O'Reilly & Associates, 2001.

Ovum 2001 Report: Pervasive Computing: Technologies and Markets, November. at http://ovum.com

Ovum 2002 Executive Briefing: Can new generation devices and MMS revitalise the mobile industry?, July, at http://www.ovum.com/events/speakingevents/default.asp?doc=july5.htm

Richard T. Pascale, Surfing the Edge of Chaos: The Laws of Nature and the New Laws of Business, Three Rivers Press, 2001.

Eric S. Raymond, The Cathedral and the Bazaar: Musings on Linux and Open Source by an Accidental Revolutionary, O'Reilly & Associates, 1999.

H. Roberts, "interviewing women: A Contradiction in terms," In: H. Roberts (editor). Doing Feminist Research. London: Routledge, 1981.

Nathan Rosenberg, Exploring the Black Box: Technology, Economics, and History, Cambridge University Press,1994.

Nathan Rosenberg, Economic Experiments, Industrial and Corporate Change, Vol. 1, no. 1, 1992

Nathan Rosenberg and L.E. Birdzell, Jr. How the West Grew Rich, Basic Books:NY, 1986.

Nathan Rosenberg, Innovation’s Uncertain Terrain, The McKinsey Quarterly, No.3, 1995.

Douglas Rushkoff, Open Source Democracy: How Online Communication is changing Offline Politics, Demos, 2003. at http://www.demos.co.uk/opensourcedemocracy_pdf_media_public.aspx

Douglas Rushkoff, Nothing Sacred, Random House, 2003.

Joseph Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, 2nd ed., George Allen & Unwin Ltd., London, 1943.

Joseph Schumpeter, Capitalism in the Postwar World in Essays of J.A. Schumpeter, ed. Richard V. Clemence, Addison-Wesley: Cambridge, Mass., 1951.

Joseph Schumpeter, Business Cycles, McGraw-Hill: NY, Vol.1, 1939.

Samantha M. Shapiro, The Dean Connection, The New York Times, December 7, 2003. at http://www.nytimes.com/2003/12/07/magazine/07DEAN.html

George Soros, George Soros on Globalization, Public Affairs Ltd, 2002.

Ralph D. Stacey, Managing the Unknowable: Strategic Boundaries Between Order and Chaos in Organizations, Jossey-Bass, 1993.

Ralph D. Stacey, Strategic Management and Organisational Dynamics: the challenge of Complexity, FT Prentice Hall, 3rd edition, 1999.

David Stark and G. Neff, Permanently Beta: Responsive Organization in the Internet Era, in P.E.N. Howard and S. Jones (Ed.) The Internet and American Life, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2003.

Teece, D.J., Profiting from technological innovation: implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy, Research Policy, vol.15, 1986.

Alan Toner, Digital Diassembly: Unzipping the World Summit on Information Society, Metamute, July, 2003. at

Siva Vaidhyanathan, Anarchist in the Library, Basic Books, 2003a.

Siva Vaidhyanathan, The new information ecosystem, June, 2003b. at http://www.opendemocracy.net/debates/article.jsp?id=8&debateId=101&articleId=1319

Thorstein Veblen, Why is Economics not an Evolutionary Science, reprinted in The Place of Science in Modern Civilization and Other Essays, Huebsch, 1990.

Ken Wilber, A Theory of Everything: An Integral Vision for Business, Politics, Science and Spirituality, Gateway, 2001.

Dave Winer, The P in P2P, DaveNet Userland, 2000, at

http://davenet.scripting.com/2000/09/09/thePInP2p

F. Zweig. Labour, Life and Poverty. London: Gollancz, 1948.